GlideQuery Perks, Part 0: What’s wrong with GlideRecord?

September 14, 2024, update: The “Spooky action at a distance” section of this article has been significantly edited for clarity and accuracy. See the footnote in that section for more detail.

When I first encountered GlideQuery, for a brief moment I naively assumed it was a complete modern replacement for GlideRecord and I got really excited. I was quickly disappointed when I learned it’s just a wrapper for GlideRecord. As such, I thought it must have all the same drawbacks and limitations, and for a while I admit I was an unbeliever and a naysayer. But, as I learned more, I realized GlideQuery is one of the best things that ever happened to ServiceNow. I’ve been using it exclusively for nearly two years and I hope through this new series of articles I can convince you to switch if you haven’t.

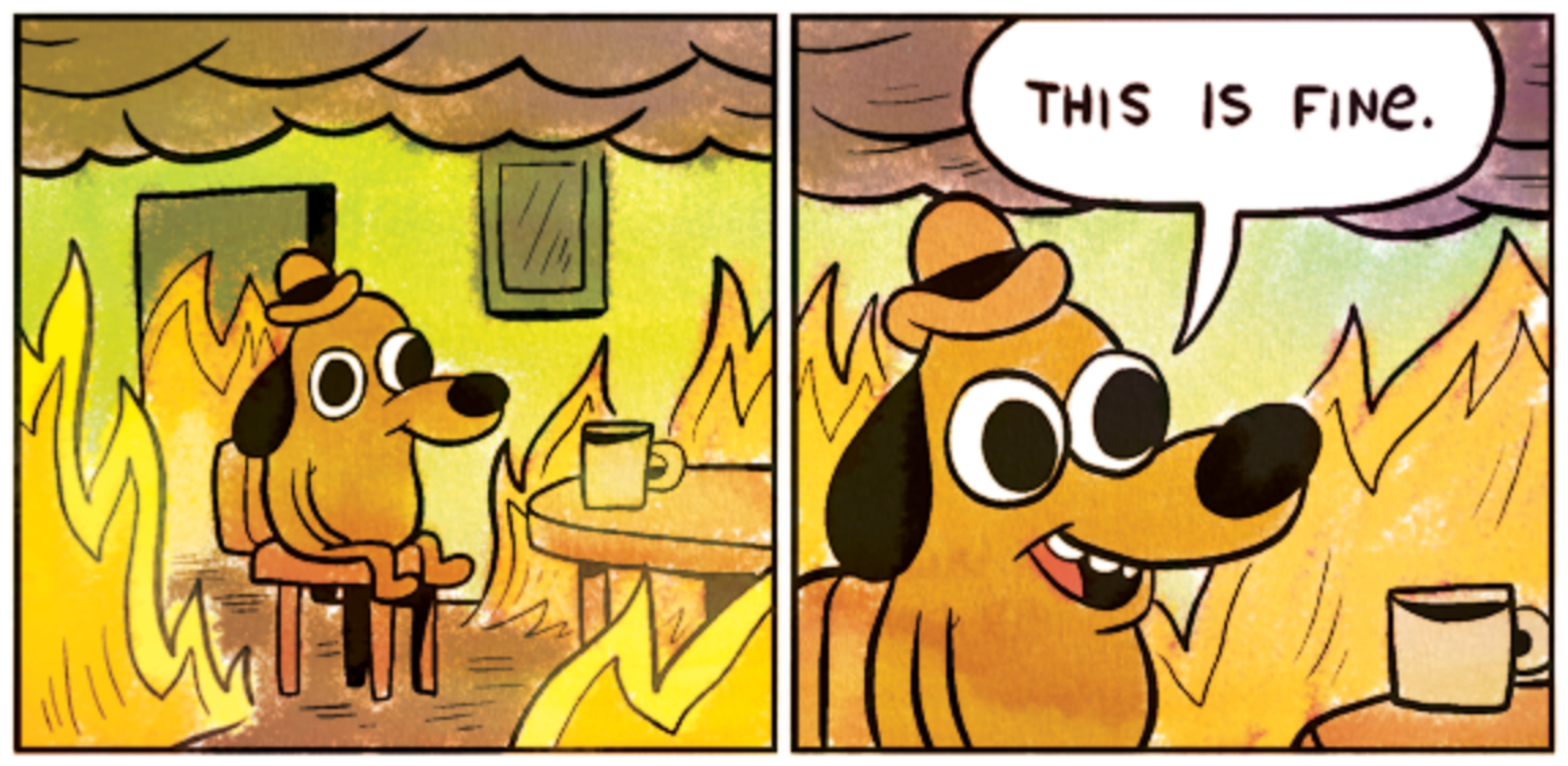

Before I talk about GlideQuery, though, I want to begin the series with a preface of sorts (hence, “part 0”) to enumerate and explain the downsides and imperfections of GlideRecord. Why have I been hoping for years something new would come along? Isn’t GlideRecord fine? If it ain’t broke, why fix it?

GlideRecord isn’t SQL

Common complaints I’ve seen around the interwebtubes any time someone compares GlideRecord to SQL are that GlideRecord can’t do stored procedures, atomic transactions, or set operations. Furthermore, GlideRecord can’t select for specific columns; instead it always returns all the columns in a given table.

It’s always annoyed me that in GlideRecord logical OR takes precedence over logical AND, which is backward from every other programming language and query language I know. Incredibly, there’s not even a way to force AND to take precedence over OR without using encoded queries, and, even then, you can’t go more than a couple levels deep with nested AND’s and OR’s. It’s remarkable this particular limitation doesn’t prevent us from getting anything done at all.

If you know me you know I love to gripe about GlideRecord’s poor support for joins. First, GlideRecord joins can only add additional where clauses to filter the returned records; you don’t actually get any columns from the joined tables in the result set. There’s no support for encoded queries in the join clause, so if you’re trying to load the join query from a conditions field on a table, no soup for you. (I stumbled on a few Community posts recently about a ^JOIN operator in encoded queries, but I’m pretty sure those aren’t supported in conditions fields either.) Lastly, I’ve seen buggy behavior depending on the precise order of the addCondition and addOrCondition methods used in the join clause.

All of the above are considered core competencies of nearly all SQL-like query languages. Comparatively, GlideRecord just doesn’t cut the mustard.

GlideRecord isn’t JavaScript

A major source of confusion and bugs in ServiceNow development is that GlideRecord just doesn’t behave like a JavaScript API. GlideRecord is actually a Java object cleverly disguised as a JavaScript object through the magic of the Mozilla Rhino JavaScript engine. Rhino is the engine that parses and executes all JavaScript scripts on the ServiceNow platform, and it has some pretty neat tricks up its sleeve, one being the ability to share Java objects into the JavaScript environment.

But since GlideRecord is a Java object, it behaves in some… unpredictable ways.

One of these strings is not like the others

var gr = new GlideRecord('incident');

gr.get(incidentID);

var text = 'How did this get here I am not good with computers';

gr.description; // How did this get here I am not good with computers

text; // How did this get here I am not good with computers

gr.description == text; // true

gr.description === text; // false (!)

Shenanigans like these made me give up on strict equality after a couple months using GlideRecord, though I really wish I hadn’t. So what’s going on here? Why doesn’t strict equality work?

Strict equality in JavaScript tests not only for equivalence of the values, but also that the types of the variables are identical. We’re pretty sure gr.description is a string, and fuzzy equality works, so why does the strict comparison fail? Because it’s a Java string, not a JavaScript string. Yep, let that one sink in for a minute.

typeof text === 'string'; // true

text instanceof Packages.java.lang.String; // false

typeof gr.description === 'string'; // false

gr.description instanceof Packages.java.lang.String; // true

getValue to the rescue?

Now, if you’ve done ServiceNow development for any length of time you’re probably screaming at the screen right now, but Joey, what about getValue?, and you’re not wrong! Calling getValue here will ensure we get back a JavaScript string, which is why most people, myself included, have adopted the best practice of always using the getValue and setValue methods rather than accessing and assigning to columns directly.

typeof gr.getValue('description') === 'string'; // true

gr.getValue('description') === text; // true

But, believe it or not, this might not always be what we want. For example, if we want to directly use a true/false column in a conditional, the Java boolean type will work just fine:

if (gr.active) {

// Only executes if active is true

// ...

}

Note that strict equality won’t work when comparing Java booleans to JavaScript booleans, but at least Java booleans are evaluated correctly for truthiness and falsiness in conditional statements.

typeof gr.active === 'boolean'; // false

gr.active instanceof Packages.java.lang.Boolean; // true

But in this case if we strictly adhere to our best practice and call getValue instead, we’re bound to be disappointed.

if (gr.getValue('active')) {

// Always executes, even if active is false

// ...

}

This is because for the true/false field type getValue returns either string '0' or string '1', both of which are truthy. We’d have to coerce this to true or false somehow for it to work properly.

Spooky action at a distance

One last issue I want to highlight is one you might be familiar with, but the first time you see it, boy, it’s a doozy.

var arr = [];

var gr = new GlideRecord('incident')

gr.setLimit(10);

gr.query();

while (gr.next()) {

arr.push(gr.description);

}

Looks simple enough, right? We’re looping through ten records and pushing the descriptions onto an array. What could go wrong? But some of you are already smirking because you know what’s going to happen. For some reason, this code produces an array with ten identical values, all ten the description from the last incident in the result set. If we debug inside the loop and inspect the descriptions, we can verify the values are fine when each one is pushed onto the array. Something’s changing them after the fact, but what, and why? For this we have to understand the difference between primitive values and objects in JavaScript.1

Primitive values in JavaScript like strings and numbers are immutable (unchangeable) and complex values like arrays and objects are mutable (changeable). If you’re not sure about this or it feels counterintuitive, I highly recommend Just JavaScript by Dan Abramov (my co-author Dan Ostler originally shared this with me), a series of lessons that gave me foundational mental models for JavaScript I never realized I needed.

But knowing primitive values are immutable and objects are mutable doesn’t give us enough information to see what’s going on in the array example above. We learned earlier that gr.description is a Java string so it should be immutable, shouldn’t it? (And, through my own testing, Java strings do seem to be immutable like JavaScript strings.) The unlock here is realizing that, strangely, simultaneously, it’s also a GlideElement object. And after a moment’s reflection this makes perfect sense. After all, we can dot-walk to helpful properties and methods like gr.description.canRead(), so it must have been an object all along.

// ¿Por qué no los dos?

gr.description instanceof Packages.java.lang.String; // true

gr.description instanceof GlideElement; // true

So somehow it’s both an immutable primitive value and a mutable object. This is some real Schrödinger’s cat quantum superposition arcane witch magic, and I don’t fully understand how it works, but I have a theory. I should point out it’s actually common in Java for an object to have more than one class through object-oriented polymorphism, but the Java classes for String, Integer, and Boolean are “final” classes, meaning they can’t be sub-classed and they’re not interfaces that can be implemented, so as far as I know no custom Java object can ever masquerade like this as a String. In researching this question I’ve read more Rhino documentation than I want to admit, and I can’t confirm this, but it seems plausible to me this behavior could be enabled by a Rhino feature called WrapFactory, which allows you to intercept when JavaScript code calls a Java object and return different values or objects based on custom logic.

Anyway, mysterious Rhino magic aside, what’s really going on is, each time the loop repeats and gr.next() is called, this two-headed hydra of an object isn’t getting replaced with a new object, it’s simply getting mutated, and since each of our array elements has been assigned the same object, they each appear in the end to have the same identical value. And the fix, of course, is the same as before: just use getValue to pass the primitive string values into your array, as this will guarantee they won’t/can’t be mutated by the call to gr.next().

GlideRecord’s use of Java types instead of JavaScript types and the counterintuitive dual nature of GlideElement objects make GlideRecord confusing to work with and—although adoption of various best practices can mitigate this somewhat—all-too-commonly introduce hard-to-troubleshoot bugs into your code.

Conclusion

I really tried not to exaggerate anything above, but even so I’m sure I managed to sound like an infomercial. I’ve only identified the problems I’ve encountered myself with GlideRecord, and GlideQuery doesn’t fix all of them—I won’t hold it up as a silver bullet or miracle pill. It does, however, fix a handful of additional issues with GlideRecord that weren’t even on my radar until GlideQuery showed me a better way. Even if none of the above gets you rankled up, I hope you’ll stay tuned to learn all the ways GlideQuery might be able to take your development on the ServiceNow platform to the next level.

Next in the series: Part 0.5: Resources →

-

The first published version of this article attributed this problem to the difference between pass-by-value and pass-by-reference. While these aren’t entirely unrelated concepts, they do turn out to be pretty irrelevant (JavaScript is actually a call-by-sharing language; actual pass-by-reference is even goofier). I also had some business in there about memory and pointers which may or may not be at all true, especially since different implementations of JavaScript are free to handle memory in different ways. Some implementations might make copies of primitive values as I described, but some might do something called value interning where multiple variables assigned the same primitive value could actually point to the same place in memory so the value only needs to be stored once. Anyway, there’s a lot of misinformation out there about why this particular GlideRecord problem happens, and I’m sorry for previously contributing to that misinformation. ↩